Special Report to Travel Markets Insider prepared by Luke Stockton, Counter Intelligence Retail

Historically, or for the last four years at least, international outbound capacity from China to the USA has surpassed overall growth in available seats departing the country, but in 2018 we have witnessed a reversal of fortunes for China’s sixth most popular destination.

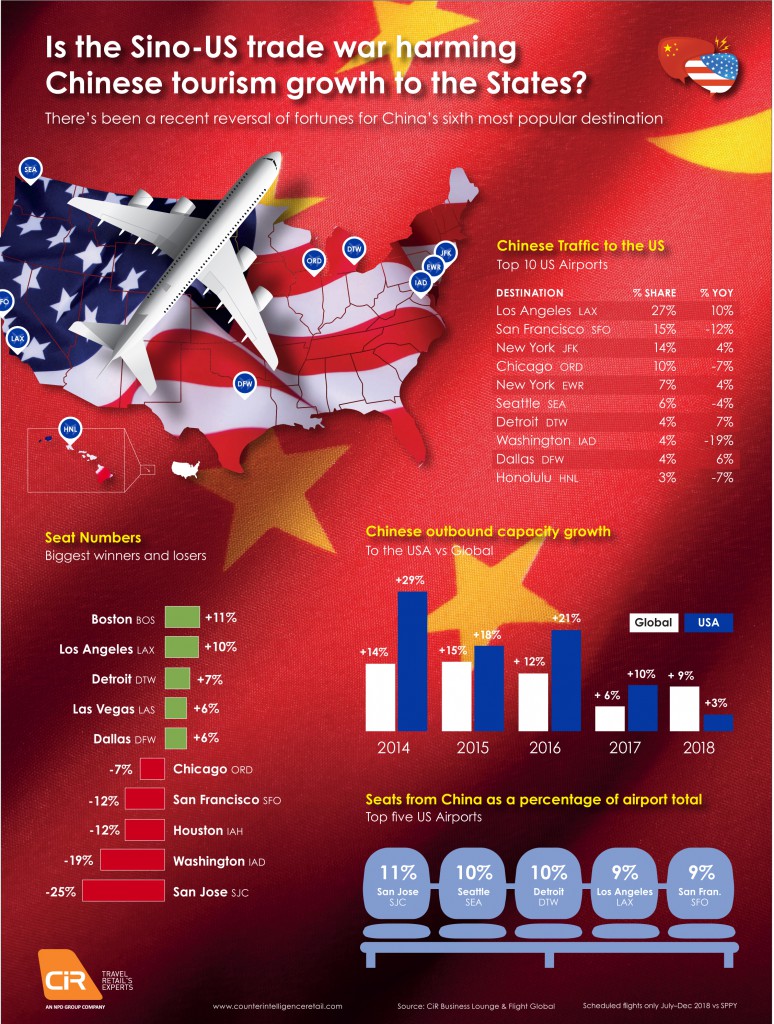

Despite Chinese international capacity growth of +9% in 2018, an acceleration from the +6% seen in 2017, growth into the States has displayed the opposite trend, slowing from +10% to +3% in 2018, and in doing so has fallen below the global average for the first time in five years.

So it begs the question, what is causing the recent downturn? Is the hostile relationship developing between China and the USA beginning to negatively impact air traffic between the two countries? And which U.S. airports stand to lose the most?

In March this year, in retaliation to claims that China employs trade practices that involve – among other things – stealing the intellectual property of American companies, the Trump administration signed a memorandum that would impose tariffs on up to US$60 billion of Chinese imports. What’s more, recent reports suggest that the U.S. president plans to go ahead with further duties on roughly US$200 billion more worth of Chinese goods, which will no doubt further escalate the already intense trade battle between the world’s two largest economies.

Looking at the data, in the first six months of the year capacity into the U.S. actually displayed robust growth (+5.8%). It is only as we have entered the second half of 2018 that growth has slowed significantly (+1.1%). Of the sixteen U.S. locations that welcome direct flights from China, the number one airport – West Coast mega hub LAX – accounts for over a quarter of the total inbound seats, and despite the slow growth into America overall is displaying healthy double-digit growth in the second half of 2018. Boston (although off a much lower base rate than LAX) is currently showing the highest growth, while Las Vegas is also surpassing the average. JFK and Newark in New York, as well as Detroit and Dallas, are in growth, although at a more modest rate.

Worryingly, however, is that five of the top ten destination airports are in negative growth. The locations to be hit hardest currently are San Francisco (-12%) and Washington Dulles (-19%) which are both experiencing significant double-digit declines. Outside the top ten San Jose (-25%) and Houston Intercontinental (-12%) are also displaying large declines, while Chicago O’Hare, Seattle Tacoma, and Honolulu, although more moderate, are also in negative growth.

It is also necessary to examine the potential exposure of U.S. airports to a significant downturn in or – worst case scenario – ban on Chinese arrivals. Trump has threatened to impose tariffs on virtually all US$500 billion worth of goods that the United States imports from China, and while Xi Jinping has thus far retaliated in kind with tariffs of his own, U.S. exports to China amount to just $130 billion, meaning Beijing could be forced to look further in order to effectively strike back at Trump’s latest announcements; a travel ban of sorts isn’t completely out of the question.

China has a clear track record of using tourism as a foreign policy tool within Asia. To name but a few examples, in a display of its disapproval of Taiwan’s new independence-leaning government China was swift to restrict the number of Chinese group tours to Taiwan. Likewise, South Korea’s well-publicized decision to deploy THAAD – the U.S. anti-missile defense system which China believed to double as an intel gathering tool – resulted in a similar set of repercussions from which the country’s tourism and duty free industries are still recovering.

Of course, the U.S. is much less dependent on Chinese arrivals than the likes of Taiwan and South Korea. That said, the importance of Chinese tourists for duty free sales in many markets is well-publicized, and a collapse in the number of potential high-spenders in their terminals would be a hit to any airport. For the majority of the U.S. airports in question, inbound seats from China account for a relatively low proportion of total inbound international capacity – anywhere from 1-6% – and as such these locations would be less susceptible to any moves by the Chinese government to disrupt the tourism flow to the States. For some, however, Chinese inbound traffic accounts for an ominously large share. For San Jose, Seattle and Detroit, for example, direct inbound flights from mainland China account for 10% or more of total international capacity, while even at the much larger international airports of LAX and San Francisco the share also stands at around 9%. For these locations the current simmering political situation poses a much more substantial risk, should it boil over any time soon.